“You have really lost it… this is above and beyond the call of crazy and you have completely lost your mind…” That is what the small, rational part of my brain was trying to tell the rest of my being in 2002 as I boarded a plane to start my career as a professional hunter in Africa. All hunters have experienced various states of insanity at one stage or another but seldom has it taken place on such a grand scale – and in a setting as interesting as Mozambique. Ten years later I still attribute my success and abilities as a Professional Hunter to the first two years that I spent in Mozambique and the experience acquired in the wilderness of the Zambezi Valley.

GETTING THERE

Two weeks prior I had submitted my letter of resignation. My family and the multimillion dollar company that I worked for was stunned; according to Dr. Askew (my father) that was the exact moment that my mind disappeared. I was 23 years old with a degree in Biology behind my name and a secure well paying job in America. I was 2 people removed from the president of the company and they were busy grooming me for more responsibility. By most people’s standards I had it made. Unfortunately, I never cared much for what most people thought, and I needed more out of life than a steady pay check and a house in suburbia. With this in the back of my mind I packed my bags and left my life in America. The adventure and challenges awaiting me in Africa would shape my life from this point forward.

The hunting company I signed on with put me in a land cruiser with the steering wheel on the wrong side and pointed me North to Tete Province Mozambique. I traveled with another apprentice hunter, he had been to the area once before and somewhat knew the way. After a final night out in South Africa we took off to find the ‘camp’ in Mozambique. The so called camp didn’t technically exist yet. Our instructions seemed pretty basic – we were to drive into the area, find the head professional hunter, and do whatever he said for the next six months. I was excited with the prospects of encountering animals that I had only read about and experiencing the ‘Big Leagues’ of hunting. We passed through Biet Bridge, then Harare, and continued north to the tiny border town of Mucumburo. The border posts, police road blocks, donkey carts, crashed and burned vehicles, mud huts, and machine guns were enough to open my eyes to the fact that this was definitely ‘old Africa’ and not some safari lodge outside of Cape Town. This was exactly what I had been wishing for.

Eventually we made it to the site where the camp would take shape and I met Leon – the head Professional Hunter and operations manager for Mozambique. He was an experienced professional, hard worker, and a great teacher. After the first week I was convinced that he was the right guy to learn from. I set my mind to soak up every bit of his knowledge about Africa and hunting. I asked him no less than 100 questions a day for the next year; he answered all of them truthfully and from experience. There was little he didn’t know about hunting in Africa.

I also took note of what a great and fast disappearing opportunity it was to be training as a Professional Hunter in this type of wilderness. We were building camp, opening new roads, and generally exploring a vast government concession. The hunting concession had pockets of local people, pockets of game, and a lot of space in between. As most all areas in Mozambique it had been hammered by poaching. Mozambique had just started to recover from the turmoil that left it ranking amoung the poorest countries in the world. This part of Africa was unforgiving and extremely difficult to operate in. It was a blessing in disguise to learn under these tough conditions; you had to know exactly what you were doing to keep a safari on track, the equipment rolling, and your client happy.

Evidence of Mozambique’s long civil war was still visible. There were bullet riddled vehicles disabled on the side of the road (casualties of a Renamo ambush during the war). There were still areas we couldn’t traverse due to the left over land mines. The place reeked of history and adventure. Not to mention the elephants, leopards, hippos, and huge crocs that we were after.

THE HUNTING

All the areas in Tete province / Lake Cahora Bassa are tough to hunt. I mentioned that earlier but it’s worth saying again. The area was very large with a low density of animals. The animals with huntable populations were Leopard, Elephant, Croc, Hippo, Bushbuck, Impala, Sharpes Grysbok, Warthog, Bush Pig, and Duiker. The area had a few Lion, 50 Buffalo, few Sable, and fewer Roan. We saw and shot a few of these but they shouldn’t have been issued on the quota. I also saw caracal, serval cat, and possibly 2 wild dogs passing through. The better hunts that we conducted in that region were croc and hippo combinations, traditional baited leopard hunts, and elephant hunts.

The croc and hippo hunts there were a slam dunk and we shot some monster crocodile and fantastic Hippo. Instead of baiting the crocs we preferred to scout the banks from land or by boat. The water level of the dam dictated which method would be the most effective. The idea was to find a place where a big croc was sunning itself. If left undisturbed, they will frequent the same mud banks to warm their cold blood. We then set up an ambush or planned an attack to sneak within range. I learned to have a great deal of respect for the survival instincts that the crocodile has refined since the time of the dinosaurs (many of these crocs were so big they seemed somewhat prehistoric and I estimate their ages to be well into their 70’s if not older). They can see as good as most antelope, but often you can trick them by moving extremely slow even in plain sight. They can smell very well and approaching a large croc downwind is a must. They listen to the shore bird’s warnings and I believe they can feel vibrations through the ground and in the water. You often see the biggest crocs with part of their body still in the water even when sunning; this alerts them to approaching danger especially in the form of boats as many of the old crocs have had bad experiences around boats. It was evident how dangerous these animals can be as reports around the lake had the death toll as high as 50 people per year. I am sure that number was exaggerated but every village had a recent story about a person getting taken by a crocodile. We witnessed one of the many fatalities near our camp in 2004.

You shoot a croc in the neck. Many professional hunters and even some books promote a head shot and I feel that in most situations it is an irresponsible shot on an animal that may be three times older than the person pulling the trigger. The brain is very small and even if you manage to hit it, the muscular reaction due to this shot can accidentally send a trophy croc into the depths. They don’t float and you will seldom get any volunteers to go swimming for it. The neck is a bigger better target. A well placed shot here disables a flat dog where it lays. After a successful neck shot the only thing that works is the mouth. That’s worth keeping in mind as you shouldn’t just run up with a stick trying to prop it open for your client’s photo!

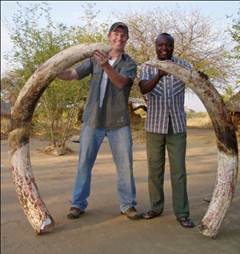

The elephant hunting was difficult, but very rewarding. We tracked these giants for many kilometers, most of the time just to turn around and return to the vehicle as the ivory was not large enough. I now have a heavy respect for this animal’s physical capability, intelligence, and its ability to hide. Some experiences were learned on the hunt and some by scouting on my own while the clients hunted with the head PH. Other good experience was gained by going on problem animal control with the government game scouts; as the elephant frequently damaged the local’s crops and grain bins. Unfortunately the elephant in this area were extra irritable due to human pressure from the war and poaching. They regularly chased the villagers and even killed some during my time there. I remember very few elephant that didn’t have an AK-47 bullet or homemade musket ball lodged somewhere in their body. During my second year in Mozambique an elephant stepped on a land mine and blew off a portion of its foot (anchoring this animal to a long terrible death if not for the mercy killing). Leon found the animal and was forced to shoot it. On the same hunt we managed to locate and kill a 92 pound tusker. We found him with a group of five bulls. The next day, after a few hours of tracking, the animal was taken down by the German Hunter.

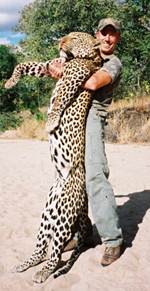

I also accumulated a great deal of leopard hunting experience in this area. I shot my first two leopards with clients in Mozambique and assisted with many others. We were constantly baiting and looking for leopard sign. Every leopard track I saw was recorded and logged away in my mind for future hunts. Due to the limited plains game and the size of the area we used goats and other live stock for the first round of baits. We tried to get the meat swinging before the clients arrived to effectively add hunting days to their safari. These Mozambique cats walked a large area and only came past the same spot every 8 – 16 days. Even if we knew where a cat preferred to patrol his territory, we most likely had only one chance to bait him on a typical 14 day leopard hunt. This caused us to bait many different cats while also hanging multiple baits for the same cat. We often had as many as 10 baits going at one time. Anyone who has leopard hunted knows how difficult it is to keep even half that many baits active. Some baits were more than a 2 hour drive apart. The amount of baits, distance between baits, and the lack of roads in the area made leopard hunting long and tiring work. Many days exceeded 14 hours of moving through the bush checking baits, making drags, building blinds, and generally searching for these secretive cats.

I learned several techniques along the way such as: to hang the meat correctly forcing the leopard to feed in a certain position so the client can get a proper shot at the animal, the practice of making scent trails to the bait intersecting the cats most likely travel routes, how to select a bait site in an area where a cat will feel comfortable enough to feed and then stick around, and envisioning the position of your blind first then working the bait position back from there. Construction of the blind and client management turned out to be a crucial aspect in the killing of a leopard. Even though the bait is usually less than 70 yards away the shot is often misplaced due to the level of excitement and nervousness of the client. A bench rest is necessary in most cases and should be built into every blind. The camouflage and arrangement of the blind is also of the utmost importance as leopard are very aware of their surroundings and are finicky at best. With these tactics and many more at our disposal the hunting of a leopard still contains a large amount of luck. However, with enough brains, baits, and hard work you can create a little of your own luck on cat hunts!

THE FUTURE

Mozambique is largely responsible for me being afloat in the hunting industry today. There I was introduced to African Hunting and to what it really means to be a Professional Hunter. I learned more about Africa from the people I met in the bush of Mozambique than any other place to date. The future of Mozambique can be fantastic and I believe many areas are slowly getting back to their original state with the correct conservation plan and time. Unfortunately there are many fly by night operators and crooked deals going on in several parts of the country. There are also many problems that the Mozambican Government must address, such as corruption and the non importation of legally hunted ivory into the USA. The Country needs better organization pertaining to the allocation of its hunting areas and its quota system, as the current system is often abused.

The old time hunters talk about how Mozambique’s hunting was as good or better than any of its neighboring countries. I believe it can be again. With more resources, education, and assistance the Mozambican people will welcome this improvement and understand how important the countries wildlife is for its future. I still welcome any chance I can get to take clients to Mozambique; it is a beautiful country with a great history and hopefully a bright future.